No first use (NFU) refers to a pledge or a policy by a nuclear power not to use nuclear weapons. It is a means of warfare unless first attacked by an adversary using nuclear weapons. Earlier, the concept had also been applied to chemical and biological warfare.

No First Use in India’s Context

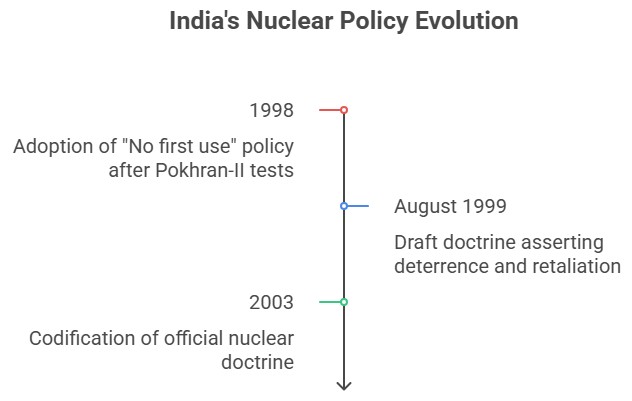

- India first adopted a “No first use” policy after its second nuclear tests Pokhran-II, in 1998.

- In August 1999, the govt. released a draft of the doctrine which asserts that nuclear weapons are solely for deterrence and that India will pursue a policy of “retaliation only”.

- India’s official nuclear doctrine is codified in a 2003 document, which takes cues from the 1999 draft doctrine.

- Since then, there has been no official communiqué about India’s nuclear policy from the government.

India’s No First Use Doctrine

Since 2003, India’s nuclear doctrine has had three primary components:

No First Use

- India will only use nuclear weapons in response to a nuclear attack on Indian Territory, or Indian forces.

- A caveat is made about their possible use in response to a chemical or biological attack.

- In a 2010 speech, then national security advisor Shivshankar Menon described India’s nuclear doctrine as “no first use against non-nuclear weapon states”.

Massive Retaliation

- India’s response to a first strike will be massive, to cause ‘unacceptable damage’.

- While the doctrine doesn’t explicitly espouse a counter-value strategy (civilian targets), the wording implies the same.

Minimum Credible Deterrence

- The number and capabilities of India’s nuclear weapons and delivery systems should merely be sufficient to ensure intolerable retaliation, also keeping in mind first-strike survival of its relatively meagre arsenal.

- It underlines NFU with an assured second strike capability, and falls under minimal deterrence as opposed to mutually assured destruction.

Cognizance with Political Authority

- Nuclear retaliatory attacks can only be authorised by the civilian political leadership through the Nuclear Command Authority.

- The Nuclear Command Authority comprises a Political Council and an Executive Council. The Political Council is chaired by the PM.

Debate on Revoking the No First Use Policy

- Raksha Mantri’s statement is a part of a pattern reflecting a need to critically evaluate India’s nuclear doctrine, as voiced by other defence ministers and retired bureaucrats and military officials.

Arguments Against Revoking No First Use

India’s image as a responsible nuclear power is central to its nuclear diplomacy

- Global reputation: Nuclear restraint has allowed New Delhi to get accepted in the global mainstream. From being a nuclear pariah for most of the Cold War, within a decade of Pokhran 2, it has been accepted in the global nuclear order.

- Say in global regimes: It is now a member of most of the technology denial regimes such as the Missile Technology Control regime and the Wassenaar Arrangement.

- Membership of NSG: It is also actively pursuing full membership of the Nuclear Suppliers Group. Revoking the ‘no first use’ pledge would harm India’s nuclear image worldwide.

A purely retaliatory nuclear use is easier to operationalize

- Nuclear pre-emption: It is a costly policy as it requires massive investment not only in weapons and delivery systems but also intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) infrastructure.

- Increase in nuclear capabilities: Similarly, first use of nuclear weapons would require a massive increase in India’s nuclear delivery capabilities. There is yet no evidence suggesting that India’s missile production has increased dramatically in recent times.

- Complete deterrence is a myth: India’s ISR capabilities would have to be augmented to such a level where India is confident of taking out most of its adversary’s arsenal and this is nearly an “impossible task”.

India would have to alter its nuclear alerting routine

- India’s operational plans for its nuclear forces involve a four-stage process.

- Nuclear alerting would start at the first hints of a crisis where decision-makers foresee possible military escalation.

- This would entail assembly of nuclear warheads and trigger mechanisms into nuclear weapons.

- The second stage involves dispersal of weapons and delivery systems to pre-determined launch positions.

- The third stage would involve mating of weapons with delivery platforms.

- The last and final stage devolves the control of nuclear weapons from the scientific enclave to the military for their eventual use.

Other Factors

- Structural changes: If India has to switch from NFU, it will have to make substantial changes to existing nuclear structures, alert levels, deployment and command and control arrangements.

- Increase in strategic weapons: This will involve a sizeable increase in delivery systems and warheads.

Arguments in Favour of Reviewing No First Use

Nuclear disarmament is still a myth

- India has been serious about nuclear disarmament.

- India’s nuclear weapons have been a result of compulsions arising out of a nuclearised and hostile neighbourhood.

- In the long-term, a nuclear weapons-free world would best serve the Indian national security interests, keeping aside moral considerations.

- A nuclear weapons-free region including China is close to impossible.

Quest for a nuclear rethink

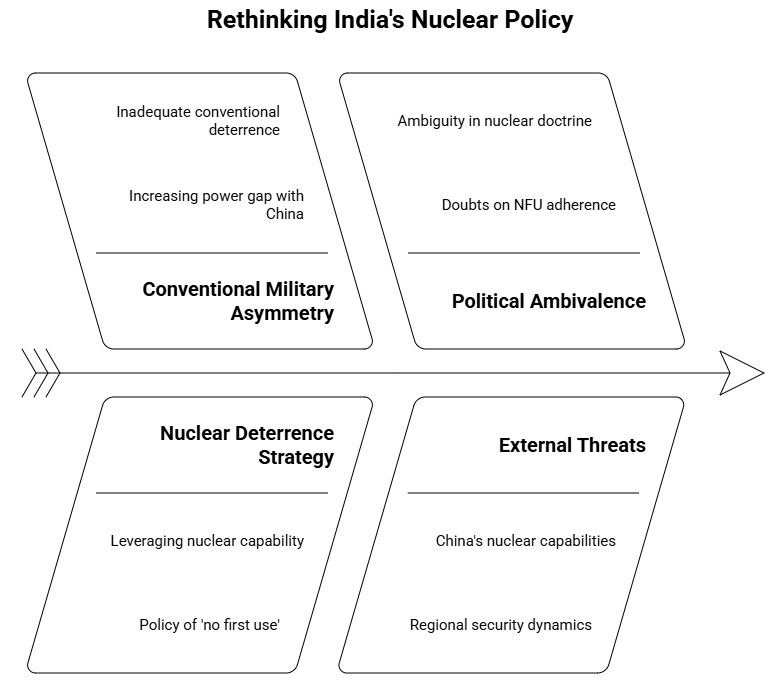

- The case to revoke the NFU pledge has also been made keeping in mind India’s other nuclear adversary: China.

- Given the increasing asymmetry of conventional military power between the two countries, some analysts believe that India should revoke its NFU policy.

- Where India’s fails to deter China conventionally, it should leverage its nuclear capability.

- In 2016, then Raksha Mantri Mr. Parrikar raised doubts on India’s adherence to the policy of ‘no first use’ by saying that New Delhi cannot “bind itself” to ‘no first use’ for eternity.

- Political leaders have tried to insert an element of ambivalence into India’s nuclear doctrine.

Advantages provided by No First Use

- Averting a nuclear crisis: The main advantage of NFU is that it minimizes the probability of nuclear use.

- More losses than wins: Instead, if both are NFU powers, there is greater probability of political leaders stepping back from the brink – for they know that a nuclear war cannot

- Significance extended to diplomacy: Notably, there is considerable convergence regarding the belief of nuclear weapons being restricted to the political realm.

Why should India not revoke No First Use?

- Havoc: The notions of revoking erroneously embrace the idea that a nuclear war can be fought and won. This is utterly false.

- No un-conventional threats: Pakistan does not pose a conventional threat that India cannot counter. Given that, they are likely to persist with terrorism, which is a low-cost option.

- Huge military investments: On the other hand, India’s conventional military power, shaped to fight a limited war, is challenged to impose its will under the nuclear shadow.

- Terrorism/Terror-state has no cognizance: Our foregoing NFU cannot prevent Pakistan from using terrorism as a tool of its India policy.

- Global credibility: On the contrary, it enables Pakistan and other adversaries to invite international intervention in what India maintains as a bilateral issues.

Evaluating the doctrine

- Success in establishing deterrence: Our policy of No First Use has many upsides, not all of them related to nuclear conflict.

- No undue celebration over nukes: The official doctrine today exists merely as a press release summarizing few points, with all other statements made offhand, with no great depth to them.

- Dialogue and diplomacy are India’s tools: Whether we have to turn to these different strategies, or simply make minor changes to our existing doctrine remains to be seen.

- Non-posturing: This debate is indicative of a larger effort of comprehensively evaluating India’s nuclear doctrine, and not only posturing.

Way Forward

- Periodic review not revocation: All doctrines need periodic reviews and India’s case is no exception.

- Non-proliferation: Indian doctrine does not support first use of nuclear weapons as it gives ample warning to the adversary of India’s intentions.

- Rational analysis of situation: If Indian policymakers do indeed feel the need to review the nation’s nuclear doctrine, they should be cognizant of the costs involved in so doing.

- Constructive debate: A sound policy debate can only ensure if the costs and benefits of a purported policy shift are discussed and debated widely.

Conclusion

As India reviews its nuclear doctrine, it is important to consider the costs and benefits of potential policy shifts and engage in constructive debate to ensure a sound and informed decision-making process.